The Kosmopolis 08 international literature fest, based at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) in October 2008, included several events focusing on JG Ballard, to coincide with the venue's 'JG Ballard - Autopsy of the new millennium' exhibition.

The main English-language event was a panel discussion titled 'Myths of the Near Future', held on Saturday 25 October at 5pm. The panel was chaired by Jordi Costa, curator of the 'Autopsy' exhibition. On the panel were Simon Sellars of Ballardian.com; writer and media critic Bruce Sterling; and V Vale of Re/Search Publications.

Following a Spanish-language introduction from Costa, Vale presented a 15-minute video detailing his relationship and work with JGB. This included a message to the festival from JGB, recorded a week earlier in Shepperton:

"Hello Barcelona. I hope everyone there is enjoying the show, if I'm allowed to call it that. Vale is taking charge of everything, and I leave him to represent me."

The following panel discussion was led by questions in Spanish, with simultaneous translation for the participants and audience members via earpiece. The discussion is here presented in the spirit of Ballard's 'Answers to a Questionnaire'.

Costa:

Sterling: I'm of the school who believes JG Ballard really is a science fiction writer, and I think he made very wise choices in the sciences he was interested in. He did in fact work on this engineering and technology publication for quite a while. He was famous for saying that the rubbish can of science was the gold mine of science fiction. That's certainly something I learned a lot from. But while a lot of science fiction writers were interested in topics like space flight and robots and atomic power and nuclear physics, Ballard was always interested in medicine, and psychotherapy, and extremes of human behaviour, and hysteria, and panic, and weapons.

I think his chosen scientific topics had more literary value than the ones that were chosen by his colleagues in science fiction. That's why his work has lasted, and that's why he was able to capture something about the nature of society that lets us use terms like 'Ballardian'. He just had a better literary understanding than most of his colleagues, a better set of tools, deeper insights that were better expressed, and that's why he's a major cultural figure while most science fiction writers are genre writers.

Costa:

Sellars: I think the adjective 'Ballardian' will become immortal, because I think that, to take what Bruce has said about the way Ballard turned from the traditional notion of science fiction from outer space to inner space, I think that was a very prophetic move. He saw the way technology was heading. There's a famous phrase of his that he wanted to explore the next five minutes rather than the next 500 years. To me, that says that he saw that technology was creating a turning inward in a psychological sense. He saw the democratisation of technology, in terms of technology that - in a phrase of Bruce's from the cyberpunk era - would stick to the skin rather than being something else. He would write abut this stuff rather than the modernist aesthetic of rockets and outer space. I think that was a very prophetic move.

Also, he saw the way that we're entering this globally homogeneous space, a sort of eventless present as he likes to call it, where you virtually can go to any country in the world. He talks about the areas around motorways and airports as a metaphor for this homogeneous space, and I think he saw the implications of where this is all heading. He also reacted against it, so I see his work as a resistance against this sort of corporate culture, and against the drive of, I guess, late capitalism to classify and categorise everything.

To me, the most important thing about Ballard is providing this space that he evokes, that preservation of inner spaces and autonomous zones. I've been reading a lot of mainstream newspaper articles recently, talking about the colonisation of inner space and the way we're really crowded with information. The terms that were used and the arguments they were making were the things that Ballard was talking about in the '60s. In that sense, I'd say there was this philosophy of resistance to a political culture. To me, that's a sort of ideal for living.

Costa

Costa:

Sterling: I think what you're asking there is, like, is his work due to date because he's a period figure. No, I don't think so. Like the work of William Burroughs, there are aspects of Ballard's work which will be very frightening and even astonishing to people in a hundred years. It's true that some things that he foresaw have become everyday things among us, but there are aspects of Ballard's work which are really intensely visionary and are never going to be seen in everyday experience, like say 'The Crystal World' disaster novel, or something goes wrong with the structure of time and people are overwhelmed by this cosmic disaster. As a young man, that was one of the touchstones of my literary experience - it's by no means a realist novel, but it had a really powerful, emotional, liberating effect on me as a teenager, just because it was showing me the scope of things that it's possible to imagine.

Ballard has a tremendous power of imagination which the passage of time is not going to be able to dim. There are topics of his which will become out-dated, like Marilyn Monroe or John F Kennedy that are going to be period figures. In a way he's a lot like Kafka - even though Kafka writes about the experience of the 1930s, when we say 'Kafkaesque', we know what that means, that no real bureaucracy will be as ideally horrible as a Kafka bureaucracy, no disaster (although we have plenty) can ever be as ecstatic and total as a Ballard disaster.

Costa:

Vale: You know, Ballard is a very wise man in his judgement, and I'm thinking that of course when he starts taking in the input of information about the financial crisis, what is he thinking about. He's not really thinking about himself, he's thinking about the welfare of his children and grandchildren, I think. Also, he knows who his audience is. I'm also a parent. This may sound strange, but he actually heartened me with his response. He more or less said to me, regarding the current state of financial chaos, downturn, whatever you call it - he said you know, I remain optimistic. I was really happy about that, regardless of whether there's any foundation or not.

I think it is important to preserve a sense of optimism and hope. In many situations, I think, one can only hope. There certainly isn't any point in just becoming very depressed, because that takes away your power, especially the power of your imagination which Ballard himself has demonstrated and incarnated in his life. He walks down the street and every time he does, it might be the same street but the street is transformed in his imagination. This is something we can all do - we don't have to take reality at face value. There has to be another dimension of inner space and inner strength we can tap, and that's got to be built up in each one of us by a sustained exercise - daily, hourly, minutely - of the imagination. Please, never take anything at face value, you never accept any of these mass media notions of reality.

Sellars: I think that's true, and that's why Ballard's books are optimistic. It's a misreading when people say they're a negative vision of the world - you hear that so often about Ballard's work. But for the reasons you say, the characters are trying to make sense of chaos, and that transforms the world.

Sterling

Sterling: I completely agree. He is a fantasist, he's not a realist writer. I find his work attractive because of the sense of liberation and inspiration and release that he gives me. Really, as a young man of imaginative bent, when I was reading these early books of Ballard in the 1960s, I was never depressed or upset by them for a moment. To me, they were one torrent of good news. They were like sunlight through a [brick?] wall in the existence I had as a young teen in a small Texan industrial town.

This is someone who really is a grand master of the imagination. Yes, he does have black humour, and yes he very much enjoys pulling the legs of the bourgeoisie, he likes to make harsh jokes at the expense of power figures, and he's really a clinician of the psychopathology of everyday life. There are a lot of things that people do in our society which are irrational and bad for us. He had a great deal of personal experience of that, and there are aspects of his own experience which are universal.

He's not a tremendously popular figure, he's not the author of 'Harry Potter', but he's by no means a minor figure. Certainly, in the circle of American science fiction writers of my generation - cyberpunks and humanists and so forth - this was a towering figure. We used to have bitter struggles over who was more Ballardian than whom. We knew we were not fit to polish the man's boots, and we were scarcely able to understand how we could get to a position to do work which he might respect or stand, but at least we were able to see that the peak of achievement that he had reached. It was not like the slough of despond, that's just a rhetorical tactic.

To call Ballard depressing, it's like a Christian fundamentalist who says 'If I didn't believe Jesus was watching me, I'd kill myself' who then argues that therefore you must be suicidal because you don't have Jesus to help you make breakfast. You're not suicidal if you understand JG Ballard. On the contrary, this guy's a consummate survivor. Burroughs and his friends and the beatnik movement had a tremendous casualty list, whereas Ballard and his friends in the British New Wave movement and the Pop Art scene were actually fairly solid, well-balanced if unconventional individuals - people with jobs and children, they were not reedy figures. This is a towering oak tree of a writer, who wrote many volumes of consistently good, accomplished work.

Many science fiction writers have - even [Homer?] nods, it's common for a writer to do something unworthy of himself and you have to overlook that. In Ballard's case, I can't think of a single work. Even his minor work is very polished, very assured - he's never hasty, he's a consummate professional, he's really in charge of every sentence on the page. It's really no accident that he's being honoured at this event. I must say that I am enjoying the show, as he urged me to do, it's a lot of fun to see this happen.

Vale

Vale: I think another thing about Ballard is, during my 32 years in publishing I've pretty much concentrated on the interview or the conversation format for a very simple reason. You don't give the questions in advance, and you just use your intuition to listen carefully and observe how the author responds in real-time to something completely unexpected and how they improvise answer. You're not even improvising if you're JG Ballard, this is just coming out of you without pause.

Really, the amount of editing I've had to do on all the people I've recorded and transcribed, the amount of editing was absolutely the least I've ever had to do with JG Ballard and, of course, William S Burroughs. Their conversations are practically extensions of their writing. I wish we could all be like that.

Sellars: Vale, can I ask did you get the sense through the interviews that Ballard was testing ideas that he would later come back to in his writing?

Vale: I don't think he tests, I really think there's almost a perfect marriage in his soul between - as soon as he starts talking and thinking and expressing himself, it's beyond some rational process level. It's just coming out, he has such an incredibly detailed and complete philosophy, such an evolved vision of the universe, unlike most of us he doesn't have to censor himself or choose his words carefully or any of that, it just comes out. One reason I like him so much is because you really think that he's considering your feelings, you really think that unlike 99 per cent of writers out there, he just tells the truth. I can't explain it any other way. I mean, how rare is that?

Costa

Costa:

Sterling: Well, I wouldn't call 'Crash' a jolly book by any means. It's a very sinister work which is well informed by a deep understanding of human psychopathology. In some ways, it's like expecting a medical textbook to be optimistic. If you read a medical textbook, it's usually a long list of terrible things that can go wrong with people. By the time you reach the end of a medical textbook, you're looking at yourself for symptoms - is it my liver, could it be my eyeballs?

I don't think that work in itself is a happy work, but when you put it down the sense of escaping that world gives you a strange uplifted feeling. It's like being subjected to a really violent massage, something on the edge of pain, and when it stops you have this sense of achievement and joy. It's like, what's the worst thing that can happen to me during the rest of my life? Will I be involved in a sexual cult involving crashed automobiles? Probably not, you know, and that's another reason to go on.

Vale: A writer often takes you - if you have an idea or a fantasy, I think you ought to take it to the utmost limit. It's only writing, it's not real life. In writing, you can kill people, you can do sexual things that you might not do in real life, but it's just writing, it's just words on paper. I think you have a duty to yourself to carry an obsession, any obsession is valid, to its utmost extension in writing, on paper, in the realm of the imagination - I'm not saying to do any of that in real life.

Sterling: I really don't think that's the ultimate extension of this particular problem. There are probably people in Nascar who are worse off than the characters in that. There are probably fans of monster racers in the United States who are more psychopathological than the characters in 'Crash'.

To me, the thing that I find really useful about that book is that most science fiction writers, if you asked them to write science fiction about cars, would write about, say, a flying car or a car that's also a submarine. They would not write about an intense psychosexual fixation with cars, or the car as another method of being, or people who are so dependent on cars they can't get through a day without cars. They certainly would not illuminate the truth about cars, which is they kill more of us than wars.

There's probably not a person in this audience who hasn't had a loved one injured or maimed or killed in a car. That's just the truth about cars, but we are very rarely shown that truth. Certainly not by the car industry. Sometimes there will be a mention of car safety in a car commercial, like your child is safe in the back seat, but you will never see a major car company of any description, from Fiat to Toyota or General Motors, apologising to the people who die in their vehicles, any more than you would see an armaments manufacturer saying, you know, I'm sorry people were killed by handguns. But it's true. It's not even like sort of true, it's kind of like a vast open scandal in our society that so many of us are murdered, I mean just slaughtered, by cars.

Sellars

Sellars: But it's very ambiguous with Ballard, isn't it, because he's also aware of the seductive nature of cars and technology and speed.

Sterling: Well, we love our cars. But there's something wrong with a society that is so in love with something so destructive. I don't even know if it is wrong, it's a statement about the nature of mankind that we love that which destroys us. We're more interested in poisonous snakes than we are in rabbits, we're fascinated by things with the potential for menace, we find them arousing and exciting. The same goes for political leaders. Really, someone who promises to simply pave our streets and look after our children will be immediately thrown aside for a person who promises us blood and sweat and tears and toil and death and a sense of exultation. Ballard talks about this openly many times, about the attractive psychopathology of cult leaders. They have command over us because they can tap into our urge to harm ourselves, and we do.

Costa:

Vale: Well, there's a huge component of theatre in everyone's life. Ballard was the first that I read to point out how the invention and widespread adoption of the cellphone has led to almost everyone becoming a sort of actor. As they talk on their cellphones in public, they're acting a lot of the time, with their gestures, and it is kind of shocking to me how cellphone users will talk about the most intimate details of their lives while other people can overhear them.

The thing is, what a book can do, it can, like, let you know in a pretty universalising way that you're not alone in any of your sexual fantasies or whatever, no matter how extreme you might have thought them. Your participation, even if just in your imagination, with these theatrical fantasies, you're just not alone. I suppose it's a form of justification to make your life easier for you. We do look to writers, I think, for help in navigating very perplexing times such as now when we have so many options for everything in our lives. What are some core values which can last when we're assaulted with so many contradictory media images, and they're usually either sexual or violent in nature, how do you sustain some kind of inner compass or barometer so we can survive all this?

Sterling

Sterling: Some of Ballard's greatest inspirations were surrealists in the '30s and pop artists in the '60s, and they were both very big on the power of the unconscious and the libido and urges which did not surface within consciousness. There was an ideal there that if you could speak to these urges directly and break the code of bourgeois behaviour and liberate something deep.

Ballard is not a sex writer in the way that say Henry Miller was a sex writer, I don't really think that's one of his major interests. He mentions it, he's kind of deploying it in the way that Max Ernst might put a nude in a collage, but there aren't really long intimate sex scenes in Ballard novels, he's not really that interested in what happens between individuals. It's more like his lasting interest in celebrity worship, which is something that shows up in his work all the time. It's like some kind of very intense social, emotional, sticky and vaguely unhealthy allegiance between people's unmet emotional needs and a figure like Jackie Kennedy or Marilyn Monroe or Princess Di. It's somebody you're never going to actually have sex with, but it's somebody who's going to come up in your erotic imaginations sort of like the Loch Ness Monster.

That's the kind of thing that Ballard finds as a totem and a touchstone. He's kind of deploying these things against us - he wants us to disrupt our sleep with these images, he's not trying like Miller to get to the core of the erotic impulse, that's not really his major line of work.

Sellars

Sellars: He also foresaw that whole anti-celebrity thing, that celebrities now don't have the lustre or starpower they used to. Those surgical fictions with Princess Margaret and Mae West where it's cutting up these celebrities in a very clinical medical way, it's very prophetic of the end of that particular paradigm.

Sterling: I've been saying Paris Hilton is a very Ballardian figure. Here you have somebody whose major reason for being a celebrity is this kind of unsought sexual transgression which was blown up through the media. It's not really like that fantastic an act of sex that Paris Hilton has, it's not like she's a sexual athlete of some kind, it's merely that she's a minor celebrity who became a major celebrity and was able to work it, to industrialise that and build upon it with the perfume and the record and clothing line and the Los Angeles celebrity life, really just construct a life out of elements of 1960s transgression.

Costa:

Sellars: It's a kind of system of circular time that Ballard uses, that sort of eventless present that's always a symbol of oppression in Ballard's work. He reuses events from history and his own personal history and re-inhabits them and re-interprets them throughout his whole career, and I think that's a very liberating force as well. It becomes a sort of parallel history in a sense, something that runs counter to the main narrative.

Sterling: I think Ballard knows a great deal about the work of the surrealists in the '20s and '30s. So much so, that he is almost a surrealist writer. He quite frequently chose surrealist canvases for his own work, and they make a lot of sense. I think he also has a deep knowledge of modernist design and urbanism and architecture. He's very aware of the roots of that in the '20s and '30s and how it developed, and the successes of the modernist programme and the failures of modernism, and the oncoming and rush of postmodernism. To be a good futurist, you need some kind of roots in the past. I think those are his roots, and those are the things he was looking at when he was quite young and he really is a scholar in those fields, and I think that has helped him a lot in his prognostications.

Costa

Costa:

Sellars: I think it's like Bruce and Vale have said, that Ballard has a surrealist background, has a very visual mindset. I think that aside from using that to explore his ideas of the subconscious and inner space, I think that in the '60s he saw how advertising was becoming basic in how we were shifting towards a visual culture. He has sort of encoded this into his writing. As we're starting to see this happen, I think that aspect of his work is becoming more and more influential and people are really picking up on that.

He is a visual person to the extent that he's created his own collages, he's starred in his own film, and I think he was working on a theatre play in the '60s, so he was really interested in breaking the frame of his fiction to create something that was in a sense a prototype for a multi-media society, and he was doing that a long time ago. If you look at that visual work that Ballard did today, the collages, they're still very strong graphic works that really re-use the tricks of advertising against itself. When I started up the website, that's an aspect that really interested me a lot, and we started to find a lot of examples of people who were really quite influenced by that. We're still continuing to find a lot of people who are really influenced by that aspect.

Sterling

Sterling: I think he has a great friendliness for the artist. Like his short story collection 'Vermilion Sands' is set in a future art colony and he takes artistic work seriously. I think artists and musicians respond to that. When they find a novelist who thinks that painters are important, they think well of him. Whereas most science fiction writers are much more in love with scientists than they are with artists, Ballard is the kind of guy who would actually go hang out with pop artists and go to their openings and befriend them and be kind to them and chat things over with them and learn with them and trade things with them. He was never a philistine, he's actually quite sophisticated in that way, and still has the dapper look of a '60s pop artist gentleman in his neat little kitted-out white suit and snappy white fedora. He's won the friendship of people in other lines of work.

Vale

Vale: He has constructed a whole universe and whole world, and the world always needs a soundtrack. What would this be - it would not be something mainstream so much as something unusual. Grace Jones at one end and you could have Joy Division at the other, and in the middle there's the Teddy Bears Picnic. The thing is, the spectrum of music is - I have to confess I'm going to reveal a small secret, I hope she doesn't mind, but Claire Walsh did tell me that she suggested one of the numbers on the [Desert Island Discs] list, one of the 10 pieces on the list was actually suggested by Claire Walsh as a sort of prank. They certainly puzzled me, those two classical pieces, which is where it's at to me. You always want to have an aspect of mystery about everything you do, even if it's by chance that something happens. I think Ballard, again as a surrealist, is very open to the miracle of a chance encounter or a chance suggestion. He is open to that, in the same way the surrealists were.

Sterling: He's someone who doesn't just facilely admire Dali or Ernst, he's actually read Dali and frequently quotes Dali. I think he probably learned quite a lot from Andre Breton. Similarly, I read Andre Breton because I thought Ballard took him seriously. Many people say Breton was a rather downbeat figure as well, but that was certainly not what occurred to people in Breton's immediate circle. They all called him the torch who lights our steps, they considered him an organising and enlightening figure, not someone who was on the fringe of society but someone who was leading them into sunlit uplands.

I think that comes across very strongly in his work, he's not really interested in the arts, he's interested in how artists think and how they approach reality, and that's what gives him a well-rounded sensibility. There are a lot of pop writers and comicbook writers and so forth who are very into pop music, and heaven knows cyberpunks love rock and roll, but to have a whole wider sensibility that really appeals to a great many people in many different lines of creative work, it's more like surrealism which is almost a philosophy, a way of life, rather than a painting, a poetry, a form of sculpture, a form of music, that's a way of being.

Vale: I agree with that. Surrealism is definitely a way of life, a philosophy, a consciousness with historical art roots that's something living, the potential is far from extinguished. You just have to read the hundreds of books, that's a start. Most people - they didn't get taught surrealism in my art history class. I hope things have advanced since then.

Costa

Costa:

Sterling: Stunned, the audience stares at one another...

Audience question:

Sellars: Only if we read more Ballard books, it's the only way...

Sterling: I really think probably the critical moment in Ballard's literary life was the two years he spent in Canada, when he was in the Royal Air Force in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He described his period at this air force base as being paralysingly boring, and the only outlet he found there were copies of these American pulp science fiction magazines which by some strange accident had ended up on this military base. You have to imagine this young very asocial man who's basically flunked out of medical school and joined the military, and having lived in China is now in an icy camp somewhere in Canada reading American science fiction for a lack of any other alternative. From that experience which is frankly rooted in boredom we get the greatest literary artist of the science fiction genre, and probably the most visionary science fiction writer of the 20th century. Boredom can be the seed of great things.

Vale: Well, the imagination is obviously the antidote to any boredom, and it's always there ready to be deployed. Imagination and brains are our secret resource which makes everyone in the audience an artist, because in your dreams you're a complete film director, you're the scriptwriter, you're the set designer, you're the make-up person, you create everything and it's all happening when you dream every night. It's really kind of a miracle.

Audience question:

Sterling: I know he enjoyed appearing as an extra in his own film. In 'Empire of the Sun', there's a period where Ballard appears in the movie as an older figure. He's always lived in Shepperton which is quite close to the Shepperton film studios which in Britain are famous for the films that are made and the sets that are made. But I don't think he's either disturbed or enthusiastic about it, I think he's had a very mature response to his unsought cinematic success. I don't think he was either disappointed or shocked or chagrined. He did the wise thing by letting Hollywood do what it wanted.

Costa:

[applause]

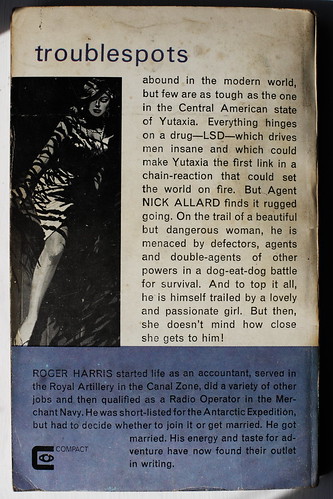

More pictures from Kosmopolis and the Autopsy of the new millennium exhibition

More pictures from Kosmopolis and the Autopsy of the new millennium exhibition.

Labels: odds, photos