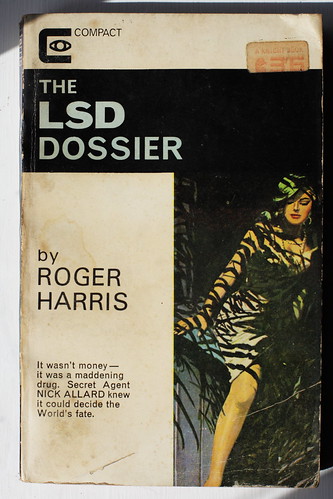

This is one of those occasional gems you can pick up if you habitually peruse secondhand bookshops – in this case, from a quick visit to that one at the bottom of Haworth's Main Street, for a princely £2.

It's interesting for at least two reasons. First (with a cap tip to

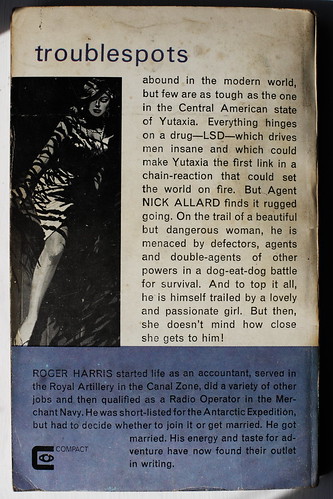

Mike Holliday for knowing about such things), it's actually (mostly) written by Michael Moorcock, a rather more noted name than the credited Roger Harris.

According to the

Multiverse Moorcock fan site, the book was originally written by Harris (though the name was possibly a pseudonym) but was more or less unpublishable. Moorcock rewrote the bulk of it because it was easier than trying to edit the prose. As Moorcock recalled:

"LSD Dossier wasn't my title, of course, and Roger Harris was a real person non-too-pleased with my revisions which mainly consisted of throwing away everything but his revised first chapter and a middle chapter and doing the rest myself."

From the evidence of the first chapter and, I'd guess, the seventh, it was a fair judgment. It does however make the author's biography on the back cover even more poignant.

Moorcock's rewrite is decidedly functional rather than some lost masterpiece. Still, as probably the rarest book by Moorcock, it can apparently fetch something over $100 from completists. So £2 well invested.

But it was the other aspect of the book that made me pick it up in the first place. It was published in 1966, the year that LSD entered the public consciousness in the UK.

As detailed in Andy Roberts's excellent

Albion Dreaming: A popular history of LSD in Britain, the nascent London hippy scene only really took to the drug in late 1965. RD Laing had been experimenting with LSD since 1960; and it had arrived on the mod scene around the same time, as evidenced in Teddy Taylor's 1961 novel

Baron's Court, All Change (another gem of a find for me, as I picked up a pristine copy of the 1965 Four Square paperback for a few quid at London's South Bank book market a couple of years ago).

Michael Hollingshead, who'd introduced Timothy Leary to LSD, arrived in London in October '65 and set up the World Psychedelic Centre in Pont Street, Chelsea; in January '66, a police raid failed to find any LSD but charged Hollingshead and others with possession of other drugs. The same month also saw the first happening put on by John 'Hoppy' Hopkins, the Spontaneous Underground in Wardour Street. The first LSD arrest took place in February, and the full moral panic kicked off after

London Life's expose on 19 March (

LSD – the drug that could turn on London), quickly followed up by the likes of

News of the World and

People.

Disappointingly, there's no sense of this in

The LSD Dossier. The drug and the threat are entirely foreign to London – the plot revolves around an attempted coup in a South American country, using a weaponised form of LSD, with the involvement of British intelligence driven purely by Cold War interests.

The threat involves a fungal strain of LSD-25 which grows on the leaves of banana plants (which did make me ponder potential links with the old 'mellow yellow' myth about the psychedelic properties of banana skins), with the aim of destabilising the populace of "hard-worked, hard-starved péons" and causing economic collapse.

It was dangerous – even the people Allard had known who were willing to try anything had agreed on that. Few of them would touch it after trying it once. It induced fantasies – fantastic, transcendental hallucinations, dark visions. [...] LSD-25 was capable of releasing anyone's psychotic tendencies.

Even more terrifyingly, a later twist reveals, the LSD has also been processed into a gas:

All Gila had to do was spray the countryside with LSD gas, driving all who inhaled it into insanity. They would also become addicted. [...] A single plane could drop enough of the gas into the centre to paralyse the whole of Yutaxia. What a malleable population, too, thought Allard.

In this regard, the novel does chime with the contemporary tabloid panic. LSD is immediately addictive and leads directly to insanity. (Moorcock did later apologise.)

In the book's climax – its most entertaining sequence – our protagonist is dosed with the drug as part of the expected torture.

He drifted through infinite jungles. Brightly coloured jungles in which vast, grotesque birds flew, obscuring the sky. [...]

For an eternity Allard was alone in an icy limbo where all the colours were bright and sharp and comfortless.

For another eternity Allard swam through seas without end, all green and cool and deep, where distorted creatures drifted, sometimes attacking him.

And then, at last, he had reached the real world – the world he had created, where he was God and could create or destroy whatever he wished. etc...

Fortunately, there's an antidote.

Labels: odds, review